Pathway Review – Pulp Friction

When you’re struggling, Pathway sends you a dog to help out. It’s that kind of game. You might have seen your squad massacred in the North African desert, but look! Here’s a cute puppy called Donut. He’s even got sharp teeth and the “Anti-Fascist” character trait that means he does +20% damage against Nazis. In moments like these, Pathway picks you back up and says maybe you can still complete the mission after all. Pathway is generous like that.

Heavily indebted to the genre of mid-20th-century pulp adventure of which Indiana Jones is the obvious cultural touchstone, Pathway depicts a world where the Nazis are plundering ancient artifacts to harness their powers in occult experiments and so must obviously be stopped by an international band of mercenaries. It’s a light, breezy, knock-about game of turn-based combat that understandably always wants you to succeed at killing Nazis, with or without a surprise canine companion. However, it lacks tactical depth and, while killing Nazis is a noble pursuit, its moral stance is less sure-footed when it steps into the territory of tired colonialist tropes.

The core of Pathway is in its XCOM-style combat. Every encounter is preceded by a planning phase in which you place each member of your squad onto the battlefield. Smart players can take advantage of this head start by positioning their squad to, say, rush an exposed enemy on the first turn. In an early sign of Pathway’s charitable spirit, you get this planning phase even when your squad has been ambushed and, unlike in XCOM, you’ll never see an enemy already in cover on the first turn of a fight.

During combat, each squad member can typically perform separate two actions–move and shoot, heal and reload, or some combination thereof–and much of the time an encounter consists of outflanking an enemy to get off a shot at them around whatever cover they happen to be hiding behind. Characters can also perform special actions depending on the weapon they carry and, in some cases, the skills they possess. Pistols, for example, allow for a special double-shot action that can target two enemies, while characters require specific skills to use items like grenades or medkits in combat.

And that’s about as deep as it gets, unfortunately. Aside from minor variations in clip size and range, all the guns function in much the same fashion and can drop most enemies in one to two shots. As a result, a character with an assault rifle plays no differently to one with a shotgun. The only meaningfully different weapon is the knife, not merely the game’s only melee weapon but the weapon with the highest damage potential. Since there’s no “zone of control” or “attack of opportunity” mechanic (outside a special action reserved for sniper rifles), it’s perfectly feasible to run right up to enemies, jump over their cover and attack from the adjacent square. In fact, it’s often the most effective approach, no matter how silly it looks or tactically uninteresting it becomes.

Fights can still be challenging, even on the default normal difficulty. A way of evening the odds is to have the enemy greatly outnumber you. Unimaginative, sure, but it gets the job done. At other times, some enemies will have access to special abilities that you don’t, while others can move further than your squad. These factors create situations where you’re encouraged to think several turns in advance, coordinate attacks between your squad members, and time your limited special actions.

But still, most of the time you’re not really feeling that pressure. Most of the time you’re just moving and shooting, moving and shooting, with the odd moving and knifing thrown in. Where the lack of depth is truly exposed is in the slim variety of actions on display, a failure that can be attributed to the derivative nature of each character’s skill tree. Indeed, when leveling up characters don’t earn new abilities, they merely improve existing ones; they’ll boost that chance to for a critical hit, perhaps, or beef up their HP. True, you can unlock the ability for a character to use an additional weapon, so that they can now carry a shotgun as well as a pistol, but it’s hard to get excited about that when, again, weapons don’t function in any meaningfully different way.

The lack of variety extends to the maps on which the battles take place. There is barely a handful of scenarios–Nazi camp, desert village, underground temple–and you’re served up a seemingly randomly-generated version assembled from stock parts each time you enter combat. A benefit of this approach is that you never know exactly what you’re going to get, but on the flip side, it means that none of the individual battlefields are ever memorable and they all end up blurring into one by the end of a campaign. That’s not to say the arenas are poorly designed; they’re serviceable and little more.

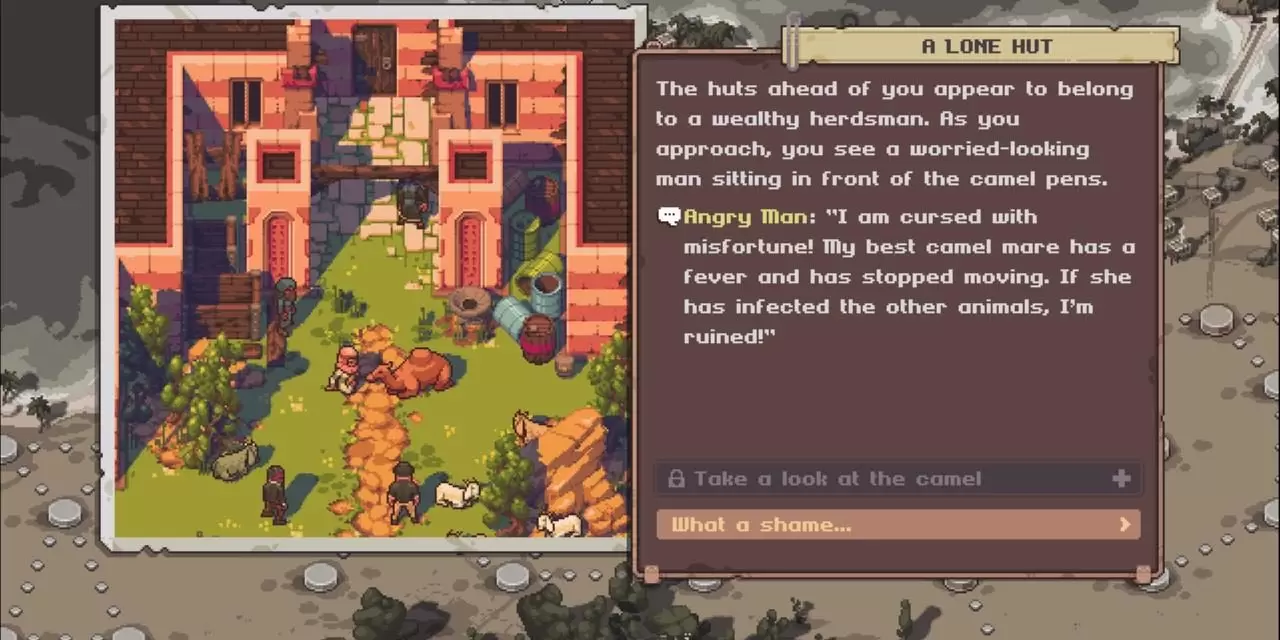

Linking one encounter to the next is a campaign structure that sees you plotting a pathway across a network of nodes. At each node, you hit a narrative event that could be anything from following some Nazis into a mysterious mineshaft to finding an oasis at which you can rest. Sometimes you might end up in a fight, sometimes you might find some treasure or a trader with whom you can buy and sell, and sometimes nothing happens at all. It’s a bit like FTL, really, except instead of zipping across space you’re driving a jeep across the Sahara.

These narrative moments are fun and typically well-written. They often allow for choices that can lead to surprising results and occasionally let you utilize the skills of one of the squad characters you’ve opted to take on the journey. But they do a poor job of depicting the African people whose countries, from Morocco and Egypt and beyond, have been invaded by the Germans. The locals you meet are helpless simpletons, peaceful goat herders at best and, at worst, cowards hiding in ruined villages and collapsed caves until you wander by to hopefully rescue them. These poor people can’t do anything until saved by a globetrotting band of wealthy adventurers.

Further, throughout the entire game, you’re collecting treasure, much of it ancient religious and cultural relics of the people you’re ostensibly helping. Literally the only thing to do with this treasure is sell it to fund the purchase of more fuel for your jeep and ammunition for your guns. Retrieve an ancient inscribed vase from the altar room of a secret temple? That goes for $250 at the next trader stop. The suggested idea is you’re keeping these precious relics out of Nazi hands, but surely there’s a better option than looting them for yourself and then selling them back to the people you stole it from.

Pathway looks and sounds great, it nails the pulpy attitude it’s aiming for, and, of course, it’s always fun to shoot Nazis. But the more I played, the more the cracks started to show, the more samey it all became, and the more uncomfortable some aspects of its design made me feel. I still enjoyed much of my time with Pathway. There’s a pleasure to be had in both its aesthetic choices and the frictionless grind of its structure, but I came away wanting more–more tactical meat in its combat and a more thoughtful approach to the way it chose to represent its world.

Source:: GameSpot Reviews